By Lauren Burns

At the age of 24 I shared with a Victorian politician how three years earlier, to my complete shock my mother had revealed that dad wasn’t my biological father. My sense of identity shattered as I discovered I was conceived with anonymous donor sperm. This member of parliament dismissed my plea for help in the search for my donor father by clapping a hand on my shoulder, ‘What you don’t know can’t hurt you.’ How wrong he was!

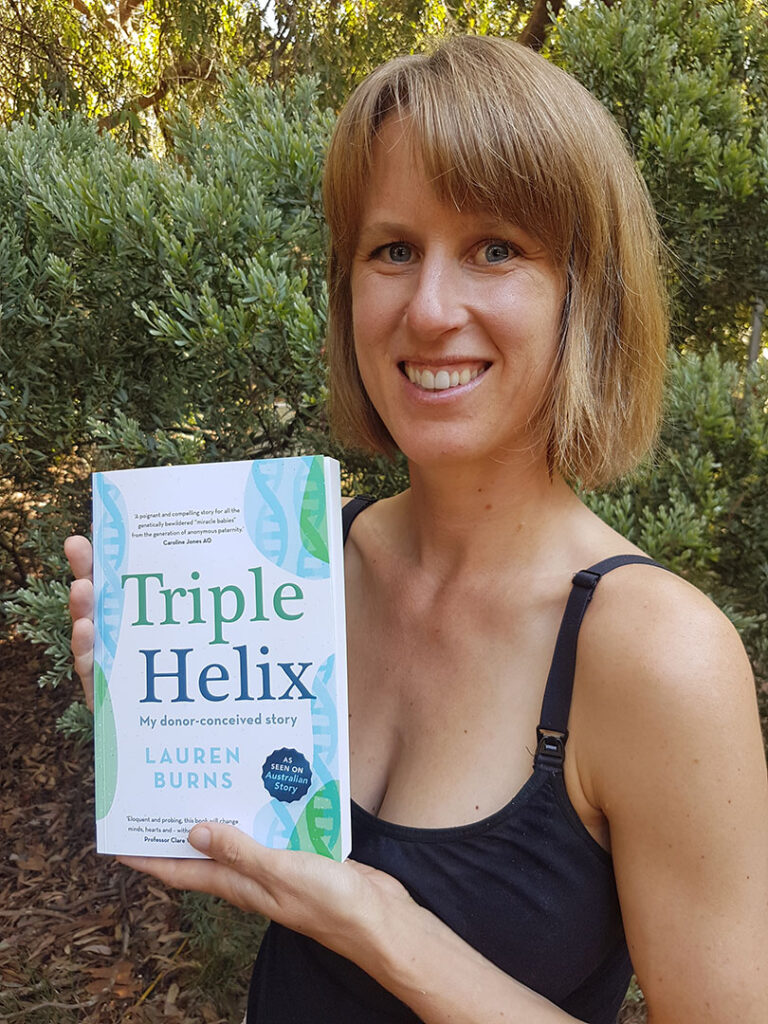

I wrote Triple Helix to answer a question I was commonly asked – Why did I need to know where I came from? For me it’s strange that people always asked that because it seemed self-evident – a human need both blindingly obvious, yet often incomprehensible to the public in the context of donor conception.

I am an engineer and writer. My life has been the story of letters and numbers. When I finished high school I received top marks in English and loved to fly. Knowing no writers, I chose the path of aeronautical engineering, perhaps because the people in my life made their living from numbers. My love of writing retreated to private journals.

My journey in search of truth began with objective knowledge. Letters and numbers formed C11 – my biological father’s donor code – the only name I knew him by. I became driven by an obsessive fever to crack this code.

Over the years my search for truth transcended into the realm of subjective understanding, a terrain studded by the paradoxical emotions and feelings brought about by my lived experiences in the absence and presence of complex family relationships.

During my PhD I was the face of my university’s marketing campaign. “My name is Lauren Burns and I am the author of my own story,” I said into the camera. But in truth I was far from in control of my destiny. The law had locked me out of ever knowing where I came from. Over the next 10 years I launched into activism to change this.

A new possibility opened up. Rather than just cracking my own donor code, was it possible that we – the people created – could work together to rewrite the source code of laws and policies governing the industry? Not just in Victoria, but on a global scale.

Engineering requires a systematic, analytical approach. It served me well in the arduous struggle to learn the truth as I battled outdated legislation, a medical culture of silence, and entered the political campaign to pass world-first laws in Victoria overturning decades of donor anonymity.

Letters and numbers. The feeling of a jigsaw puzzle falling into place when I finally received the first letter from my biological father, Benedict, and saw a family tree which mirrored my dual love of words and equations. His siblings included a maths teacher, English literature academic, and a journalist.

I learned my grandfather was the famous Australian writer and historian Manning Clark, author of the six-part opus, A History of Australia. Indeed, the Clarks were a family of writers that had published everything from poetry to biography to political analysis. I wanted so badly to write a book to convey the complex issues that can arise for donor conceived people, a perspective that has long been unknown or ignored. But it wasn’t until I discovered my connection to this literary canon that I finally felt the confidence that writing was something I could do.

So, I began the task of writing my own history – 16 years, distilled over four years of writing and editing into 269 pages. My writing method is entirely opposite to my systematic engineering process. Eschewing structure, I prefer to connect to my subconscious through dreams and meditation, then write intuitively in a stream of consciousness. Yet, there are parallels. In my day job, working to design a zero carbon aircraft, after sweating over a lengthy calculation a beautiful graph can emerge. In writing, I recognised the same feeling of flow. The transcendence when a difficult passage of the book suddenly fell into place was akin to the ecstasy of collapsing numbers into a single elegant curve. The satisfaction of making obvious what was hidden.

My biggest challenge as a writer was how to connect emotionally with a reader who might not have a personal experience of DC or adoption. The titular triple helix represents the three strands of my parentage – biological father, social dad and my mother. It’s also the DNA, experience and psychology that makes us who we are. A helix is a symbol that endlessly revolves back around itself. It seems fitting because my donor conception story wasn’t straightforward and is never really over. The structure of my book quite deliberately reflects that. It’s not written chronologically, and there are lots of twisting metaphors, like rivers and spirals.

Writers need a deadline. When I was three months pregnant I decided to stop endless tinkering and submit my manuscript to several publishers. The response was dead silence. You need to know people in the trade to get published. My cousin, writer and historian Anna Clark, introduced me to her network, and with the backing of an excellent literary agent suddenly publishers wanted to talk to me! In the midst of a global pandemic, I inked a deal with the incredibly supportive team at University of Queensland Press in February 2021 when I was seven months pregnant.

In birthing my book and human babies, the support of my partner Gerry and a small group of experienced women to play midwife to my creations was critical. In both instances the key was to remain calm and positive through the process of transition: from my comfort zone, to discomfort, to the pain zone and beyond to a transformational zone where I learned to let go and allow the strange workings of nature to take the lead.

Triple Helix explores the common question of being. Who am I? Overlaid is the radical rewriting of my personal history and sense of identity after meeting my biological father and discovering I’m connected to a well-known Australian family. It personalises a shadowy system of donor conception that has been practised for well over 70 years and created millions of people worldwide.

By elevating the importance of lived experiences, my goal is to spark a conversation about how to protect the best interests of the people created at the potent intersection of the all-consuming desire to have a child, the power of emerging biotechnologies such as genetic engineering and the assisted reproductive industry, which is growing ever larger, more global and commercialised.

My name is Lauren Burns and I am the author of my own donor-conceived story.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Lauren Burns is an aeronautical engineer, writer and advocate – one of the team who successfully lobbied the Victorian parliament to pass legislation that allows all donor conceived people to learn the identity of the donor used in their conception. Triple Helix: My donor-conceived story is available on Kindle. Readers in Australia can purchase a paperback copy here.