By Tracey Maniskas, Ed.M.

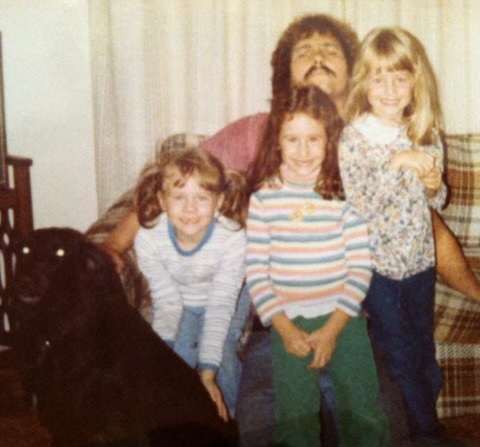

I was raised in the Philadelphia area with both of my triplet sisters, Jill and Rachel. We had always known that our parents used medication and artificial insemination to boost their chances of having a baby. However, they neglected to tell us they also received assistance from a sperm donor — for forty-two years.

When our parents divorced when we were twenty years old, their decision seemed to come out of nowhere, but we eventually adapted to our new family structure, with both of our parents remarrying within five years. When we were 41 years old, my husband and I hosted a brunch at our home for my sisters, our dad, and our stepmom. During that visit, Dad handed to each of us a printout of his ancestry composition report from a commercial DNA service, encouraging us to take a test as well. My sister Jill then submitted her DNA to the same company and although she reviewed her geographic ancestry analysis, she never looked at the family members with whom she was matched, assuming there would be no unfamiliar information.

Almost a year later, a half brother reached out to Jill through the DNA testing website. He explained that he learned that his biological father was a sperm donor and asked if she had any more information. Jill immediately questioned our mom as to how this could be, to which the response was a continued denial that this man could be a relative. However, later that day our dad admitted that they had used a sperm donor, and during that conversation, mentioned casually that they had actually mixed the donor sperm with his prior to insemination. This additional revelation opened the door to an even more complex question: Were the three of us actually full sisters? My sisters and I look completely different from each other, including hair color, eye color, and body types. We even have different blood types.

The years of secrets had done some damage to our relationship with our parents, but it was their responses to us discovering the truth at such a late age that created the majority of our anger towards them.

Once she knew that we had learned about the sperm donor, our mom insisted that Dad had been completely sterile and that no mixing had occurred. However, since she had continued to deny the truth when Jill had initially confronted her, we truly did not know who to believe. Jill had thankfully found an expedited test that we used to definitively confirm our full sisterhood two weeks later, rather than waiting the four to six agonizing weeks for the commercial DNA test results.

The years of secrets had done some damage to our relationship with our parents, but it was their responses to us discovering the truth at such a late age that created the majority of our anger towards them. Our mom was angry with us for wanting to learn more about our newly found half siblings, along with needing to identify and learn about our biological father. Our dad, who we realized had set up the situation for us to learn the truth, seemed to back away from us, and behaved like it was no big deal for us to find out that we weren’t biologically related to him and half of the family we had known our entire lives. As I had always been closer with my dad and knew that my mom would most likely never come around to understanding what we were going through, I focused my efforts on my relationship with my dad.

It was three months after learning we were donor conceived before he and I finally had a face-to-face conversation. I had been brutally honest with my dad during the minimal phone conversations we had prior to this, which had been difficult but necessary. I’m a master’s level therapist and had been through a deep depression when my parents divorced because I tried to keep all of my emotions to myself. Having both a personal and professional understanding of the necessity of honesty in communication, I laid out everything I had thought and felt throughout this journey, and listened fully to his response, which was also as honest as it could be. Although a wonderful, involved and supportive dad, he had never been great with words or verbally expressing himself. Dad admitted that he had wanted us to know the truth of our conception since we were in high school, but my mom had refused to allow that, and now at the age of seventy, he had had no idea how to tell us or how to react once we did actually learn the truth. This conversation was followed by many more like it and was truly the first step in healing from the broken trust and anger that follows a discovery like this. If I hadn’t been a therapist myself, I would imagine having a therapist to prepare me or to be present would have been incredibly beneficial.

In the meantime, through both the commercial DNA app and social media detective work, my sisters, myself, and our new brother discovered the identity of our biological father and learned that we had eight more half siblings, bringing our collective count to twelve. The donor himself had raised four children, and there were four additional half siblings between two commercial DNA websites, including a set of twins. Some of our siblings knew how we were related and some did not, and we chose to leave that alone, not knowing how to handle such a sensitive family secret.

About four months after learning that donor conception was part of my history, I was struck with the realization that I had been experiencing the stages of loss. Looking back at my thoughts, feelings and behaviors it became quite clear, but in the midst of it all, the surrealistic nature of learning such a massive truth had made everything feel like a jumbled blur.

Five of us, including my sisters, our half brother and another half sister, sent a group letter to the man we believed to be our biological father. He thankfully did respond, confirming that indeed he was, but that he had no interest in meeting us and asked that we respect his wishes. Although disappointed, connecting with my new siblings made it a little easier to process. The immediate connection we experienced was a happy surprise to us all, and getting to know some of others out in the world with whom we are biologically related created a sense of completion in our journey.

About four months after learning that donor conception was part of my history, I was struck with the realization that I had been experiencing the stages of loss. Looking back at my thoughts, feelings and behaviors it became quite clear, but in the midst of it all, the surrealistic nature of learning such a massive truth had made everything feel like a jumbled blur. During that time, I was just trying to get through each day without a breakdown, wondering what was around the next corner. Having great friends, family and a therapist to help with the process helped to remain grounded through the chaos.

For the remainder of that first year, I enjoyed getting to know some of my new siblings and their families. We did small and group dinners, traveled together, and they even attended my sister Jill’s wedding that December, with all of the siblings, except the bride, sharing a table. About a month after the wedding, I received an email from the commercial DNA company, notifying me of a new familial match which turned out to be our thirteenth sibling, a brother. Our known sibling group conferred and debated how to communicate with him and what, if anything, we should reveal about our relationship if he wasn’t already aware, which we quickly realized he was not.

The weight of this knowledge, and what to do with it, is complicated. There is no simple, right or wrong answer. One argument for telling the person that they are donor conceived is that we do have a right to know who we are, if we are giving incorrect medical information, etc. Another argument for revealing the truth was made by my sister-in-law, who argued that both of her donor conceived husband’s parents had passed away before he learned the truth, meaning he would never have the opportunity to talk with them about being donor conceived or to hear their thoughts and feelings. From my own personal experience and therapist perspective, learning that I was donor conceived created such an emotional upheaval, and as we knew nothing about our new brother or his personal health/mental situation, I was very apprehensive regarding the consequences of just blurting it out. In the end, we settled on a slow drip of information and encouraged him to ask his parents (who were still alive) if they had any idea as to how we could be related. In the end, his parents never did acknowledge the truth to him, and he had asked enough questions for us to feel that it was right to explain our connection.

When my siblings or I would tell our donor-conceived discovery story, we were always told that it sounded like a book or a movie. About eighteen months into our discovery, I read a book by a memoirist who was also in the late-discovery donor conceived club. I read her story within two days and cried for several more. Although I had not been prepared for my intense emotional reaction, it was incredibly helpful and healing to see my thoughts and feelings, some of which I hadn’t understood or could put voice to at the time, in someone else’s words. That was when I decided to write my story, in the hopes of helping others to find context, comfort, and know that they are not alone in this unfathomable experience.

I hope that my family’s story can also be a useful communication and educational resource for donor conceived individuals and their families, because there seem to be far too few available in the mainstream. A friend of mine recently recommended my book on social media, a colleague of hers read it and returned to the post to comment. She stated that her own daughter had been donor conceived, that she had simply never thought about it from her child’s perspective, finding it fascinating and helpful to consider. Looking back, I recognize how hard it is for both the children who were lied to and the parents who were instructed by their trusted doctors to lie so many years ago. I hope that my family’s story will also help the family and friends of donor conceived individuals to better understand what they are going through and how better to support them.

Another observation from my family’s experience is that we all process aspects of this discovery very differently. My triplet sisters and I, raised together since birth, all responded individually to learning the truth, accepting that our biological father had no intention of meeting us, and held different perspectives on handling an in-the-dark new sibling. Everyone’s journey is unique and needs to be respected.

Just over a year ago, our fourteenth sibling appeared. He had thankfully just learned the truth of his parentage, and with the hardest part out of the way, we happily filled him in on all that we had learned so far. Out of the fourteen of us, seven of us regularly communicate and get together. We continue to love each other’s company and just enjoy being together, which is an amazing silver lining to the wild ride many of us take when we first learn the truth of our hidden biological beginnings.

Top photo by Levi Guzman on Unsplash

Tracey Maniskas earned her master’s degree in counseling psychology at Temple University and is author of From 3 to 13… A Story of Secrets and Siblinghood, a memoir about the year following her surprising genetic discovery as she and her sisters seek to determine if they are truly full siblings, confirm the identity of their unknown biological father, and navigate their unexpected new reality, all while connecting with additional family members they never knew they had.